Is It Time For Joint Surgery? Here’s How To Know

Alison Ripa, 59, of Sterling, MA, paid a price for ignoring the pain in her left knee. When she was a teenager, she’d badly injured it in a softball game. Injured joints are often more vulnerable to osteoarthritis later in life, and sure enough, the disease developed decades later in Ripa’s knee. “My husband, my son, and my daughter all said the same thing: ‘Your knee is in a permanent bent position, and you’re miserable,’ ” she says. “I didn’t feel good, and everyone around me was being affected.” Still, she resisted having joint replacement surgery: “I tend to put pain on the back burner and just suck it up.” (Here are 6 things your joint pain is trying to tell you.)

Ripa delayed knee replacement surgery for 3 years, then finally had it done in 2010. The long wait meant she had a longer rehabilitation: It took 9 months of rigorous daily exercise to straighten out her knee postsurgery. Three years later, when Ripa’s right knee developed osteoarthritis, she knew she couldn’t afford to ignore it and scheduled a joint replacement right away. As a result, her recovery from the second procedure was speedier and easier.

Today, hip and knee replacement operations, called arthro-plasties, are fast becoming the most common elective surgeries in the US. More than 1 million joint replacements—in which part of a natural joint is removed and replaced with a prosthesis—are performed each year, an estimated 440,000 hip replacements and more than 700,000 knee replacements.

Millions of Americans now live with an artificial knee or hip. It’s estimated that by 2030, the number of hip replacements done each year will nearly double and knee replacements will increase by almost 700% as the population ages and more people want to stay active later in life. Almost all these surgeries, like Ripa’s, are performed to repair damage from osteoarthritis.

When performed at the “right” time, the surgery has a successful track record for restoring pain-free mobility. The trick, though, for both doctors and their patients, is pinpointing that time. (Here’s what happens when joint replacement surgery goes wrong.)

An estimated 55 million Americans have arthritis, a disease in which joint cartilage degenerates, usually causing pain and stiffness. Osteoarthritis—the most prevalent form—commonly affects the hips, knees, hands, and feet. In its early stages, it can be treated with over-the-counter and prescription anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle-strengthening exercises, and steroid injections.

Doctors usually recommend joint replacement surgery as a last option for patients with osteoarthritis, after other treatments are no longer effective and the pain is unbearable or mobility is severely limited. At that point, the doctor who has been treating the arthritis refers the patient to a surgeon for a consultation to see whether surgery is recommended.

Though the process sounds straightforward, it’s anything but. First, there are no agreed-upon guidelines to help primary care doctors and their patients make that decision. Specialist medical organizations such as the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons have guidelines to help their members advise patients on surgery timing during a consultation. But prior to that point, there are no standards to help the medical community at large—the internists and family practitioners who treat many cases of osteoarthritis—understand what degree of joint damage, pain, or impairment in day-to-day activities signals the right time to advise a patient to consider surgery.

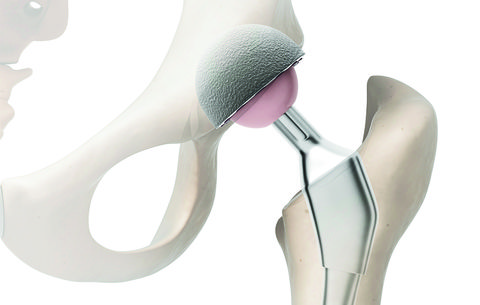

HIP REPLACEMENT SURGERY: THE BASICS

HOW IT’S DONE: A surgeon removes the hip’s ball and socket and replaces it with an artificial socket plus a ball on a metal stem. The stem is placed inside the top of the thighbone, which is hollowed out with a drill. A liner keeps the new ball gliding smoothly within the new socket. The surgeon can cut through muscle using an anterior (from the front), lateral (from the side), or posterior (from the back) approach, making a small or large incision. (Here are 9 things no one tells you about getting a hip replacement.)

PAIN/RECOVERY: The length of the hospital stay ranges from 1 day in an ambulatory surgery center to several days, depending on the degree of osteoarthritis, age, health status, and more. Postsurgery care includes at least 1 week of physical therapy, home exercises, daily walking, and painkillers as needed.

IT’S ESTIMATED THAT HIP REPLACEMENTS WILL NEARLY DOUBLE AND KNEE REPLACEMENTS WILL INCREASE BY ALMOST 700% BY 2030.

Nicole Dorsey, a 53-year-old copywriter in Orange County, CA, believes she waited too long to have the surgery, even though she was only 45 when she had her first hip replacement. With her strong family history of osteoarthritis, it wasn’t surprising that her hips began to ache at a young age.

By the time she turned 43 in 2007, the pain in her right hip had gone from tolerable to agonizing. She took anti-inflammatory medication five times a day to cope and went for deep tissue massage and acupuncture. Still, the pain became unbearable. “I could limp around but not walk normally,” she says. She had to stop exercising and teaching yoga.

Dorsey’s doctor told her the disease had worn away the cushioning cartilage in her hip, and bone was rubbing on bone. Terrified that the surgery might worsen her mobility or cause her to become less active for months afterward, Dorsey endured until 2009, when she finally resigned herself to having her hip replaced. She’s glad she did. “I was able to return to exercise and teaching yoga quickly,” she says. “And 6 months after the surgery, I felt awesome—running, doing yoga, doing lunges, the works.” (Open up your hips and feel the stretch with these 12 yoga poses.)

Five years later, when arthritis Five Dorsey’s left hip to become as painful as her right had been, she didn’t hesitate to have another replacement. Even though the recovery was longer and more difficult the second time, Dorsey’s only regret, she says, is waiting as long as she did to have her first hip replaced. “Ignoring the arthritis meant I was damaging my own femur, chipping away at what was left of the bone where it connects to the joint,” she says.

Many patients, like Dorsey, are willing to endure the pain because they’re afraid of the surgery itself—and often of the pain and recovery period afterward. Other patients, especially younger ones, may postpone the operation because they want to minimize the chances of needing to have the joint replaced again—most prostheses last about 20 years.

Surgeons want more patients to realize that there are perils to waiting. “Doing the replacement is harder when arthritis is more advanced because there is more deformity and more bone loss,” says Michael Mont, chair of the department of orthopedics at Cleveland Clinic. “And your function gets worse, so it makes rehabilitation harder.”

In effect, waiting may mean that you could wind up more limited after surgery. “Don’t tell yourself that it’s just part of aging,” says Fiona Webster, an associate professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. “It’s really important to have those conversations early.”

But having surgery too early is also problematic. Roughly a third of knee replacements examined in one study were performed inappropriately early, and the people with less-severe osteoarthritis didn’t benefit as much from the surgery as those who had more-damaged knees. A second study of nearly 7,500 men and women with osteoarthritis also found that those whose symptoms were relatively mild benefited only minimally from replacement surgery. The challenge, for doctors and patients, is finding the sweet spot for surgery, when the disease is advanced enough that new joints will bring dramatic improvement but not so advanced that damage to the joints and muscles will make surgery and recovery less successful.

[…]